In the evolving landscape of global cinema, few industries have risen as rapidly and forcefully as Nollywood—the Nigerian film industry. Rich in cultural expression, narrative complexity, and social influence, Nollywood is now ranked among the world’s most productive film sectors, second only to India’s Bollywood in terms of output.

However, with such reach comes enormous responsibility, especially in the portrayal of religious symbolism. In recent times, Nollywood and its allied digital spaces—particularly content creators on platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram—have increasingly ventured into a deeply troubling terrain: the use of Catholic imagery, vestments, and rituals in profane, comedic, romantic, or outright offensive contexts. While it is true that most of these vestments are not obtained from the Church nor officially consecrated, they are often meticulously designed to mimic Catholic priests, bishops, and religious sisters.

These imitations include cassocks, Roman collars, stoles, mitres, pectoral crosses, the Aspergillum (holy water sprinkler), and even the confessional. Regardless of their origin, their misappropriation reveals an alarming ignorance or disregard for the sacred, and a deep insensitivity toward one of the world’s most symbolically rich religious traditions. Catholic vestments and religious attire are not mere garments—they are outward signs of an inward and sacred reality. The Church teaches that vestments participate in the sacramental mystery of worship and carry the weight of ecclesial meaning. As stated in the General Instruction of the Roman Missal (GIRM), “Sacred vestments should contribute to the beauty of the sacred action” and “be a sign of the ministry exercised by each of the ministers” (GIRM, 2011, nos. 335–337).

They serve a dual function: to conceal the personality of the minister and to manifest the office he holds in the divine liturgy. To parody these garments or use them in profane comedy, sensual skits, or secular films is not simply an aesthetic error—it is a sacrilegious assault on a theology of presence. Although the vestments used in these productions may not be liturgically consecrated, their visual and symbolic proximity to authentic Catholic vestments is the heart of the offense. The actors may not step into a Church to borrow a real chasuble, but the deliberate design and mimicry imply a conscious intent to represent Catholic clergy or religious life.

Such imitation, particularly in comic or romantic contexts, distorts not only the garments but the roles they symbolise. When a skit features a woman in a mock religious habit engaging in romantic or suggestive behaviour, or a man in a fake cassock using the confessional for humour, it desecrates sacred space through symbolic violence. These images trivialise centuries of consecrated life, reduce the priesthood to a joke, and distort the sacrament of reconciliation. The Catechism of the Catholic Church condemns this unequivocally: “Sacrilege consists in profaning or treating unworthily the sacraments and other liturgical actions, as well as persons, things, or places consecrated to God” (CCC, 1997, para. 2120). Even when the vestment is not technically “sacred” by blessing, its use to impersonate the sacred renders the act sacrilegious.

This misuse is particularly grievous in the case of the confessional. This sacred space, defined by secrecy, healing, and divine mercy, becomes the site of mockery when actors depict false confessions or manipulate the act of absolution for comic relief. In such cases, what Nollywood and skit creators are engaging in is symbolic degradation of the sacrament of penance—a sacrament rooted in the blood of Christ and administered through apostolic succession. As the Rite of Penance notes, “Through the ministry of the Church, God grants pardon and peace to the penitent” (Rite of Penance, 1975, no. 46). To turn such a sacred act into a sketch undermines the trust, reverence, and humility required of the faithful. This practice is not merely offensive to Catholics; it is intellectually lazy and morally bankrupt.

The semiotics of Catholicism—its gestures, postures, signs, and icons—are among the most visually compelling in the religious world. As Romano Guardini writes, “In the liturgy, everything is sign and everything is real” (*The Spirit of the Liturgy*, 1935, p. 21). To employ these signs for shallow comedy or irreverent scripts is to evacuate them of their meaning while capitalizing on their mystery. This is not creativity but cultural plagiarism. It exploits the Church’s symbolic capital while mocking her spiritual patrimony. Moreover, the use of these imitations in Nigeria’s volatile religious environment is not without consequence.

In a country marked by ethno-religious tension, where religious identity is often interwoven with politics, community belonging, and even safety, the careless portrayal of religious leaders can ignite public outrage or deepen sectarian divides. Respect for religion in public discourse is not only a theological imperative but a civic duty. Saint John Paul II, in his Message for World Communications Day (2002), warned against media that “reduce religious belief to the level of entertainment or ridicule” and called for portrayals that “respect the sacred and the transcendent” (no. 6). One cannot discuss this trend without indicting the theology of art and its ethical bounds.

The Church, far from being anti-art, has long championed the artist’s role in revealing divine beauty. In Letter to Artists, Pope John Paul II affirms, “The artist is a witness to the invisible” (1999, no. 3). However, this role demands reverence. Authentic art elevates; it does not denigrate. It purifies; it does not pollute. When a Nollywood film presents a drunken “bishop” or a flirtatious “nun” under the guise of humour, it fails both as theology and as art. This is where the words of Hans Urs von Balthasar ring with prophetic urgency: “Only the beautiful will save the world” (The Glory of the Lord, Vol. 1, 1982, p. 18). But beauty here is not cosmetic; it is the radiant splendor of truth and goodness.

Misrepresenting Catholic signs in profane contexts betrays this triadic unity. It not only blasphemes but educates poorly. For the audience— many of whom are ill-catechized or religiously impressionable— these representations shape theology through entertainment, often producing distorted ecclesiologies and unhealthy skepticism toward the Church. The law of the Church also speaks directly to this misuse. Canon 1171 of the 1983 Code of Canon Law states: “Sacred objects, which are designated for divine worship by dedication or blessing, are to be treated reverently and are not to be employed for profane or inappropriate use even if they belong to private persons.”

While Nollywood may bypass the letter of the law by using unblessed replicas, they cannot escape the spirit of this canon. The reverence demanded of sacred representation does not end with the sanctuary—it must be observed in every public engagement with the sacred. The Catholic Church in Nigeria cannot afford to remain silent. There is need for an articulated document on the portrayal of the Catholic faith in media, backed by juridical and moral principles, and supported by diocesan media offices. Content creators should be offered workshops on religious literacy. Filmmakers with Catholic background should act as cultural witnesses, correcting false narratives with artistic integrity.

Likewise, seminaries and Catholic universities should integrate courses on media literacy, cultural semiotics, and liturgical theology—so that the next generation of priests, sisters, and scholars are not only guardians of the sacred, but interpreters of culture. The time has come for Nollywood to mature—beyond cheap laughs, into thoughtful representations. Sacred symbols should not be objects of ridicule but thresholds into mystery. The cassock is not just a long robe; it is a habit. The habit is not just a uniform; it is a sign of consecration. The confessional is not just a wooden box; it is a throne of mercy.

When these are mimicked irreverently, society loses its anchor to the sacred, and art degenerates into abuse. The issue at stake is not just about vestments—it is about vision. Will Nollywood choose the path of reverence or ridicule? Will it engage Catholicism as a sacred narrative or as a source of parody? The future of religious culture in media may depend on this choice. Let us not forget the words of Tertullian, who declared: “The things of God are to be handled by the hands of God”. The sacred is not a stage prop; it is the dwelling place of the divine. Let Nollywood beware, lest in mocking the symbols of Christ, it unwittingly crucifies Him again—not on a Roman cross, but on the podia of public comedy.

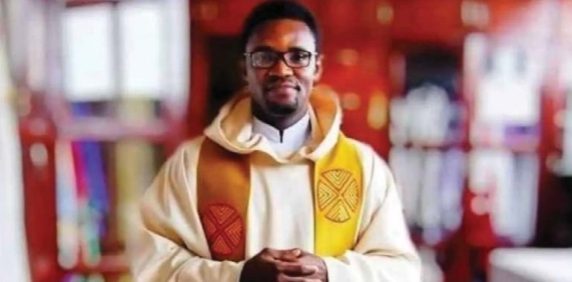

• Rev. Fr. (Dr.) Okhueleigbe Osemhantie Ãmos is a Catholic Priest of Uromi Diocese and a Lecturer at the Catholic Institute of West Africa, Port Harcourt, Nigeria