As a New York Times investigation ignites outrage, denial, counter-accusations and bitter recriminations, Nigeria is once again thrust into the global spotlight over one of its most explosive and painful questions: Are Christians being systematically targeted for annihilation, or has the world been misled by propaganda, flawed data and politicised advocacy? Neta Nwosu reports

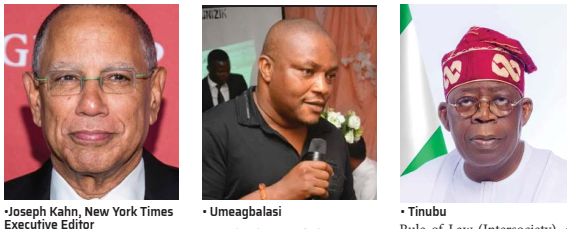

Nigeria’s long-running insecurity crisis has collided head-on with global media power, diplomatic pressure and domestic politics, following a controversial New York Times report that questioned the credibility of claims that Christians are facing genocide in the country. What has followed is not merely a dispute over statistics, but a full-blown war of narratives involving civil society groups, socio-cultural organisation, the Presidency, former lawmakers, international lobbying firms and a besieged rights organisation at the centre of the storm. At the heart of the controversy is Emeka Umeagbalasi, founder of the International Society for Civil Liberties and Rule of Law (Intersociety), an Onitsha-based human rights organisation that has, for years, documented killings, abductions and attacks on Christian communities, especially in northern Nigeria.

The New York Times portrayed him as an “unlikely and controversial” source whose data—allegedly drawn from secondary reports, internet searches and advocacy groups—had been cited by influential US politicians to push the idea of a Christian genocide. The American newspaper’s report suggested that Umeagbalasi’s work helped shape US perceptions that culminated in dramatic diplomatic and military consequences: Nigeria’s redesignation as a “Country of Particular Concern” under US religious freedom laws, fiery rhetoric from then US President Donald Trump about an “existential threat” to Christianity in Nigeria, and eventual US airstrikes against ISIS targets in Sokoto State in December, reportedly at Nigeria’s request. The fallout has been swift and ferocious.

HURIWA: ‘A $9 million propaganda war’

Leading the counter-offensive against the New York Times report is the Human Rights Writers Association of Nigeria (HURIWA), a prominent civil society group, which has dismissed the report as “uneducated, unintelligent propaganda” allegedly sponsored by the Nigerian government. HURIWA claims the report is a direct consequence of a $9 million lobbying contract allegedly linked to the Tinubu administration, aimed at polishing Nigeria’s image abroad and discrediting reports of Christian persecution. According to HURIWA, documents filed with the US Department of Justice show that DCI Group, an American lobbying firm, was hired through Aster Legal on behalf of the National Security Adviser, Nuhu Ribadu, to communicate Nigeria’s actions in protecting Christian communities.

For HURIWA, the irony is staggering. “The same government that publicly denies that Christians are being targeted,” the group argues, “is spending millions of dollars to convince the United States that it is protecting Christians.” The organisation ridiculed attempts to undermine Umeagbalasi by repeatedly describing him as a “screwdriver trader,” insisting that such attacks insult the intelligence of Nigerians and trivialise the gravity of mass killings. HURIWA further stressed that evidence of attacks on Christians does not rest on one individual. It pointed to widely reported atrocities, including the massacre of worshippers at St Francis Catholic Church in Owo, Osun State, a case so clear-cut that Nigerian security agencies are prosecuting suspects.

It also recalled testimonies by senior Catholic figures, notably Bishop Wilfred Anagbe of Makurdi, before US congressional panels, as well as fact-finding visits by American lawmakers to affected communities across northern Nigeria. In blunt language, HURIWA declared the New York Times report a “failed propaganda,” insisting that the genocide narrative cannot be erased by attacking one source. “The killings are notorious. They are reported globally. To pretend otherwise is to lie to the world,” the group said.

Intersociety fights back

Intersociety itself has rejected the New York Times report in equally strong terms, accusing the newspaper of falsification, misquotation and what it described as a “perfidy of lies.” The organisation flatly denied claims that its founder admitted to not verifying data or relying casually on Google searches. According to Intersociety, its data collection involves both primary and secondary sources, including field researchers, volunteers and direct engagement with affected communities. It insisted that it documented about 19,100 church attacks since 2009—not “close to 20,000” as reported—and that its estimates were carefully qualified.

The group also denied allegations attributed to Umeagbalasi regarding kidnapped Kebbi schoolgirls and inflammatory remarks about Fulani communities, saying such statements were never made during the hours-long interview conducted by the New York Times reporter. For Intersociety, the issue is not just reputational damage but the broader attempt to delegitimise years of documentation of violence against Christians. It maintains that Boko Haram and allied jihadist groups have disproportionately targeted Christian populations, particularly in earlier years of the insurgency, contrary to claims that Muslims were the majority of victims.

Ohaneze flags danger over explosive Igbo, ISIS claims

The apex Igbo socio-cultural organisation, Ohanaeze Ndigbo, has issued a blistering warning to The New York Times, accusing the American newspaper of publishing a dangerously misleading report capable of triggering ethnic unrest across Nigeria. Reacting to a recent New York Times story suggesting that Igbo individuals provided intelligence that led to US airstrikes against ISIS targets in Sokoto, Ohanaeze said the publication was not only false but “potentially incendiary,” with the power to inflame tribal tensions in an already fragile nation. In a statement released in Abakaliki, the Deputy President-General of Ohanaeze Ndigbo, Mazi Okechukwu Isiguzoro, categorically rejected any claim that Igbo people were involved in intelligence gathering or military operations connected to the United States’ counter-terrorism campaign in Nigeria.

“The Igbo are not, and have never been, participants or intelligence providers in US operations against terrorist networks,” Isiguzoro declared, warning that such allegations could provoke suspicion, hostility and violence against Igbo communities, especially in Northern Nigeria. He also dismissed the claim that Igbo groups were the driving force behind the narrative of Christian persecution in Nigeria, even though Igbo Christians have been among the victims of attacks. According to him, a broad range of non-Igbo organisations, faith groups and diaspora-based civil rights bodies have been at the forefront of drawing attention to the plight of persecuted Christians. Ohanaeze was particularly outraged by the New York Times portrayal of an Onitsha-based “screwdriver seller” as a key intelligence source for US airstrikes. Isiguzoro described the account as “absurd, insulting and deeply dangerous,” warning that it echoes the kind of propaganda that fuelled ethnic hatred ahead of the tragic events of 1966.

“This is the same toxic playbook that branded the January 15, 1966 coup an ‘Igbo coup’ and paved the way for pogroms and genocide against our people,” he said. “To suggest that a trader from Onitsha was pulling the strings of US military action is not only laughable but a clear attempt to resurrect the age-old scapegoating of the Igbo.” While commending the collaboration between the United States under President Donald Trump and the Nigerian government in combating terrorism, Ohanaeze firmly rejected any attempt to drag the Igbo into security operations or covert intelligence narratives. The group demanded an immediate and unreserved apology from The New York Times and called for the article to be retracted, warning that the newspaper would be held responsible for any escalation of tensions the report may trigger, particularly in Northern Nigeria.

“Ohanaeze is not opposed to US–Nigeria cooperation against terrorism, nor to efforts to improve Nigeria’s international image,” the statement added. “But we will not tolerate any revival of anti-Igbo propaganda that has historically been used to sow division and bloodshed.” The organisation also urged Igbo civil rights groups to refrain from commenting on sensitive US–Nigeria security matters, cautioning that such remarks could be twisted to justify what it described as a reckless and dangerous media narrative. “This time,” Ohanaeze concluded, “we will not be silent while history is being rewritten to make the Igbo convenient scapegoats once again.”

Shehu Sani: ‘A comical tragedy’

From a different angle, former Kaduna Central senator Shehu Sani has seized on the New York Times report to criticise what he sees as the dangerous influence of unverified advocacy. Describing the revelations as “unfortunate and tragic,” Sani said it was shameful that claims allegedly sourced from a small NGO operator could “tense up US lawmakers, the President and the intelligence community” to the point of military action. For Sani, the episode represents a cautionary tale about how misinformation—if not rigorously scrutinised—can distort international relations and escalate conflicts.

Presidency: ‘Facts are stubborn’

The Presidency has welcomed the New York Times report as vindication of its long-held position. Daniel Bwala, Special Adviser on Policy Communication to President Bola Tinubu, declared that the narrative of Christian genocide was a hoax, allegedly pushed by the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) and amplified internationally. Bwala said he had warned as early as August 2025 that the claims were false and politically motivated, and argued that the New York Times investigation confirmed that conjecture and bias were presented as fact. The government continues to insist that Nigeria’s violence is not religiously targeted, noting that Christians, Muslims and adherents of traditional religions have all suffered at the hands of terrorists and bandits.

A nation caught between pain and politics

What this bitter dispute ultimately exposes is Nigeria’s deep wound: tens of thousands dead, communities shattered, and trust eroded—between citizens and government, activists and authorities, Nigeria and the world. Whether the term “genocide” is accepted or rejected, the bloodshed is real. Churches have been attacked, mosques destroyed, villages erased, and faith—of all kinds—has been tested. The danger now is that the debate itself becomes another battleground, where propaganda, denial and exaggeration drown out sober truth and urgent solutions. As Nigeria grapples with insecurity, economic hardship and fragile national cohesion, one question looms larger than all others: will the search for truth unite the country in confronting violence, or will competing narratives deepen the fractures and prolong the suffering?